Distribution of GST Revenue: the Worst Public Policy Decision of the 21st Century to date.

Australian Society and Politics, Economic Policies, The Australian Economy | 4th February 2024

An essay about the consequences of the Morrison Government’s decision (supported by the then Labor Opposition and continued, indeed extended, by the current Albanese Labor Government) to change the way in which the revenue from the GST is carved up among Australia’s states and territories, at the behest of Australia’s richest state, Western Australia.

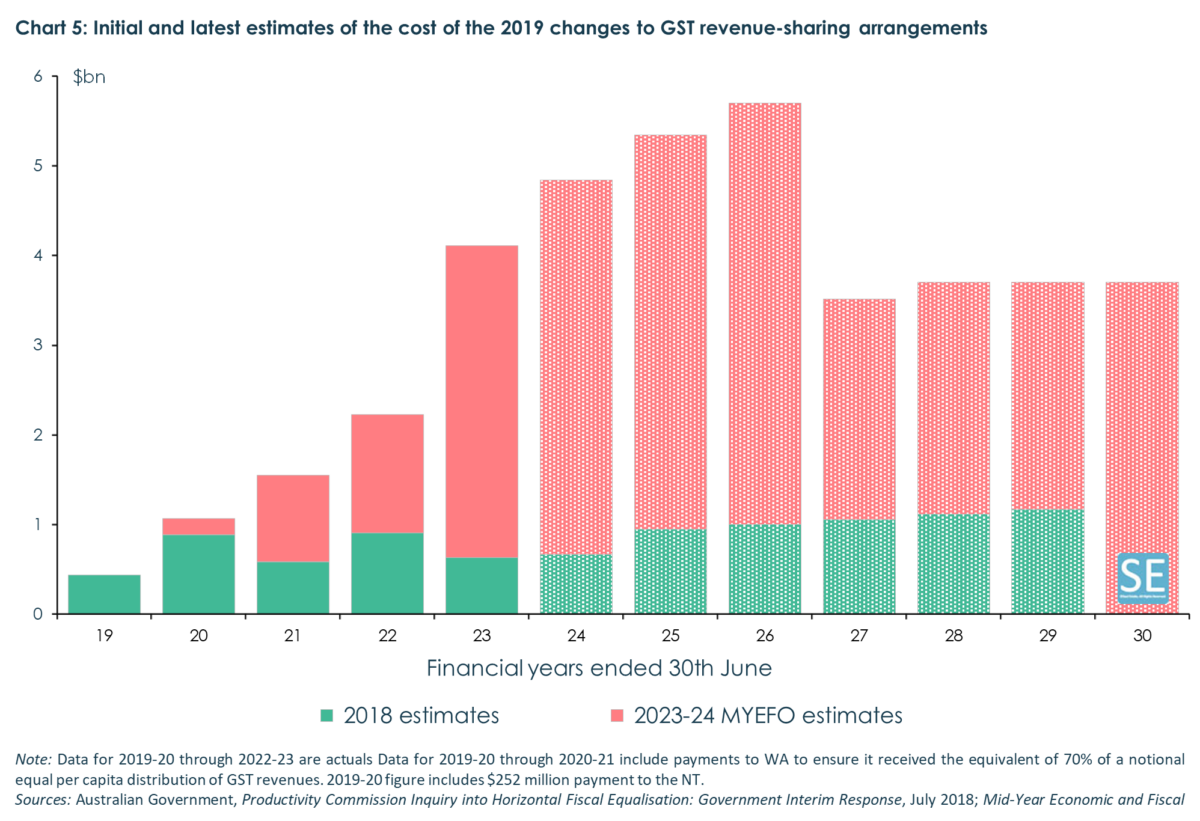

Initially, my concerns were mostly about the implications for the smaller states & territories (for whom the GST accounts for a larger share of their revenues than WA, NSW and Victoria) when the ‘transitional guarantee’ that none of them would be worse off as a result of these changes expired, as it was originally set to do at the end of 2026-27. But with that can having been ‘kicked down the road’ until 2029-30 – which in turn makes it likely that it will be kicked another three or more years down the road if iron ore prices are still above US$55 per tonne then – the issue is now more about the cost to the Federal Budget (already more than four-and-a-half-times what was originally envisaged), the corruption of the intent behind what is the biggest single expenditure item in the Federal Budget, and the equity of giving $40 billion over a decade to the richest state in Australia so that its citizens can have better public services and lower state taxes than everybody else.

the changes to the arrangements for determining the distribution of revenue from the GST among the states and territories instituted in 2019

Australia takes ‘horizontal fiscal equalization’ – the distribution of money from the federal government to the states and territories so as to allow each of them to provide roughly similar public services whilst levying roughly similar burdens of taxation – further than any other federation in the world. That’s one reason why the differences in material living standards between Australia’s richest and poorest states are much smaller than those in other federations. But the process by which this is achieved has been egregiously undermined by the changes made to the carve-up of GST revenues among the states and territories by the Morrison Government in 2019, with the support of the then Labor Opposition, and continued (indeed extended) by the Albanese Government. I regard it as possibly the worst Australian public policy decision of the 21st century thus far. But very few people understand it. This is an attempt to correct that.

The distribution of revenue from the GST to the states and territories is the largest single expenditure program in the Federal Budget. According to 2023-24 Budget Paper No 1, it will amount to $92.5 billion in the 2023-24 financial year (or 13.6% of total payments), rising to $105.3 billion (13.8% of total payments) in 2026-27. That compares with $58.9 billion in 2023-24, rising to $67.5 billion in 2026-27, in “support for seniors” (mostly the age pension); and with $41.0 billion in 2023-24, rising to $55.1 billion in 2026-27, for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. The distribution of GST revenues accounts for a larger share of total Budget expenses than the fourth, fifth and sixth largest programs (aged care services, medical benefits, and assistance to the states for health care services), combined.

So it’s important.

Yet very little attention is paid to how it’s done.

From the introduction of the GST in 2000-01 through 2020-21, the revenue from the GST was distributed to the states and territories in accordance with recommendations from the Grants Commission, which were in turn based on the principle of “horizontal fiscal equalization” which had been used by previous governments since 1981 to determine the distribution of financial assistance grants – that is, grants which the states and territories were free to spend as they saw fit, rather than in accordance with directions laid down by the Federal Government, as with ‘National Partnership Payments’, formerly known as ‘specific purpose payments’ – among the states and territories.

That principle held that financial assistance grants – or, after 2000, revenue from the GST – should be distributed among the states and territories in such a way as to enable each state and territory to provide public services of a similar range and ‘quality’ as the average of all states and territories, whilst imposing state taxes of similar ‘severity’ as the average of all states and territories. Whether any given state or territory chooses to do that is, of course, a matter for them: the objective of ‘horizontal fiscal equalization’ is that they have the capacity to do so.

In practice, what this principle has meant is that the revenue from the GST was, between 2000-01 and 2020-21, distributed in such a way as to bring the ‘fiscal capacity’ of each state and territory up to the ‘fiscally strongest’ state (or territory).

Throughout the twentieth century, the ‘fiscally strongest’ state was either Victoria or New South Wales. For most of the twenty-first century thus far, it has been Western Australia.

That’s of particular interest, because the principle of ‘horizontal fiscal equalization’ was developed in the aftermath of what, if it were to have happened in recent years, would no doubt have been called the ‘Wexit Referendum’, at which, on the 8th April 1933, Western Australians voted by a majority of two to one to secede from the Commonwealth of Australia.

Secessionist sentiment in Western Australia had been driven by the adverse impact of the protectionist policies which Victoria, as the pre-eminent colony at the time of Federation, had foisted on the new nation, to the particular detriment of Western Australia’s then, as now, agriculture- and mining-dominated economy, especially during the Great Depression.

The referendum was held simultaneously with a state election, at which the government which had promoted the referendum was defeated (with the incumbent Premier losing his own seat). The incoming government, though opposed to secession, nonetheless petitioned the British Parliament to amend the Australian Constitution (which it theoretically had the capacity to do, since it was originally an Act of the British Parliament) to allow Western Australia to secede – something which a joint committee of the British Parliament concluded it no longer had the power to do following the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931. Thereafter, the secession cause lapsed.

The 1933 secession referendum nonetheless prompted the Federal Government of Prime Minister Joe Lyons to establish the Commonwealth Grants Commission, to provide the government with “impartial and independent” advice on the distribution of grants to the states. In its Third Report, published in 1936, the Commission promulgated the principle which, from then on, underpinned its recommendations on the distribution of Commonwealth grants to states:

“… special grants are justified when a State through financial stress from any cause is unable efficiently to discharge its functions as a member of the federation and should be determined by the amount of help found necessary to make it possible for that State by reasonable effort to function at a standard not appreciably below that of other States” (Commonwealth Grants Commission 1936, page 75).

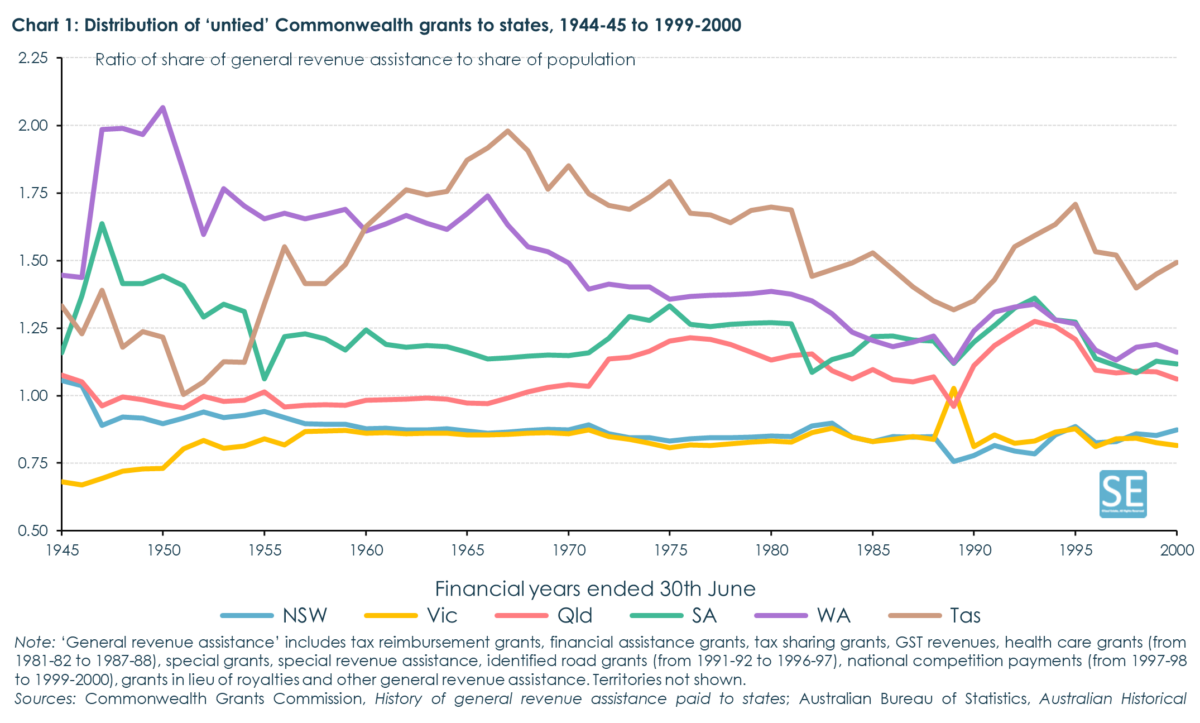

As a result of the application of this principle, and the way in which the distribution of (at different times between the Commonwealth’s assertion of a monopoly over the collection of personal income tax in 1942 and the introduction of the GST in 2000) ‘tax reimbursement grants’, ‘financial assistance grants’, and ‘tax sharing grants’ were distributed among the states (and eventually territories), for more than seventy years Western Australia received a larger share of ‘untied’ Commonwealth grants than it would have done had they been distributed on the basis of population shares, a more favourable outcome (from Western Australia’s standpoint) than for any other state except Tasmania. (see Chart 1).

That was as it should have been, in accordance with the principle enunciated by the Grants Commission in 1936, given that Western Australia incurred above-average costs in providing public services to a relatively small population thinly spread over a vast area, and that its capacity to raise revenues from its own sources was dampened by low commodity prices for most of this period (in the second half of the 1980s, for example, the iron ore price averaged less than US$12 per tonne).

But then, from about 2004 onwards, Western Australia got, to adapt one of Paul Keating’s more infamous phrases, “kissed on the arse by a rainbow”.

The iron ore price rose to over US$100 per tonne by the end of 2009, stayed above that level until mid-2014, fell to a low of just over US40 per tonne at the end of 2015, but thereafter started rising again, and has been above US$100 per tonne again for all but four months since June 2020. The prices of most of the other commodities produced in Western Australia, including LNG, nickel, aluminium and lithium, have also been much higher, on average, over the past two decades than they were in the second half the twentieth century.

In addition, there has been an enormous increase in the volume of Western Australia’s mineral and energy production since 2010. Iron ore production rose from 151 million tonnes in 1999-2000, to an average of 835 million tonnes per annum in the past six years.

The value of Western Australia’s iron ore production has thus risen from just $3.7 billion in 1999-2000 to an average of $111 billion per annum in the past six years.

The value of Western Australia’s lithium production has risen from less than $25 million twenty years ago to over $20 billion in 2022-23. The value of gold production has risen from just under $3 billion in 1999-2000 to an average of $17 billion in the past four years. The value of WA’s LNG production has risen from under $2 billion in 1999-2000 to $56 billion in 2022-23.

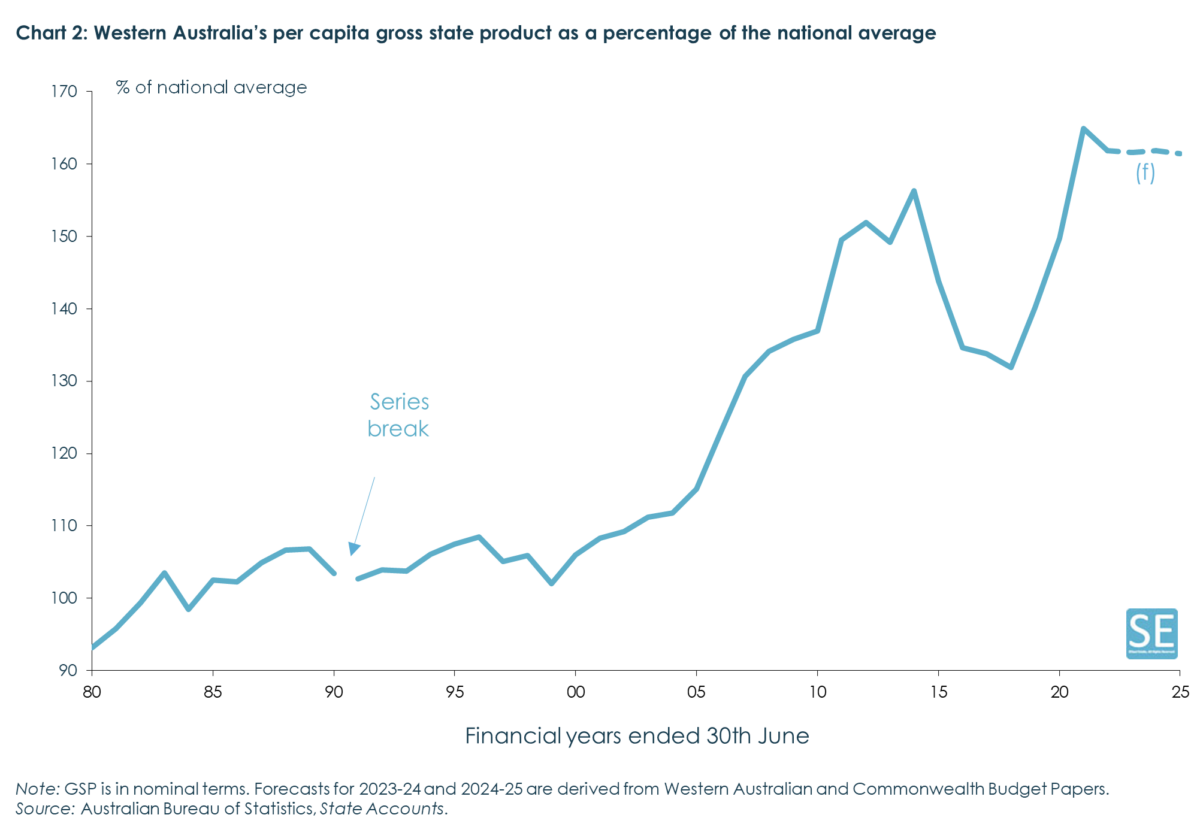

All of this (and more) has seen Western Australia’s per capita gross state product increase from around 7% above the national average at the turn of the century, to more than 60% above the national average in the past three years (Chart 2).

Put differently, Western Australia’s per capita gross product has in recent years been more than 70% above the average for the rest of Australia (what Western Australians like to call ‘the Eastern States’). To the best of my knowledge there has never been another time, at least not since Federation, when one state has been ‘richer’ – as measured by per capita gross product – than the rest of the country by as large a margin as Western Australia has been in recent years. During the past 45 years during which ABS estimates of gross state product have been available, the ACT’s per capita gross product has never been more than 24% above the national average; Victoria’s has never been more than 12% above the national average, and New South Wales’ never more than 8% above the national average.

Put differently, Western Australia’s per capita gross product has in recent years been more than 70% above the average for the rest of Australia (what Western Australians like to call ‘the Eastern States’). To the best of my knowledge there has never been another time, at least not since Federation, when one state has been ‘richer’ – as measured by per capita gross product – than the rest of the country by as large a margin as Western Australia has been in recent years. During the past 45 years during which ABS estimates of gross state product have been available, the ACT’s per capita gross product has never been more than 24% above the national average; Victoria’s has never been more than 12% above the national average, and New South Wales’ never more than 8% above the national average.

It would be surprising if during the first 75 years after Federation, any of the other states would have been ‘richer’ than the rest of the country by anything like this margin.

It’s worth emphasizing in this context that this extraordinary improvement in Western Australia’s economic position relative to the rest of Australia is overwhelmingly the result of ‘good fortune’, rather than ‘good management’.

Yes, successive Western Australian state governments have assiduously courted investment in WA’s minerals and energy resources; and some individual Western Australians have contributed significantly to bringing those resources into production. But neither the WA State Government nor any individual Western Australians put those resources under the ground, or under the seas surrounding Western Australia; nor did they drive the prices of those resources up to stratospheric levels. Most of the capital required to fund the enormous expansion of production capacity came from shareholders in the Eastern States, or overseas. And so did a good deal of the labour – either as a result of people moving to Western Australia, or on a ‘fly-in, fly-out’ basis.

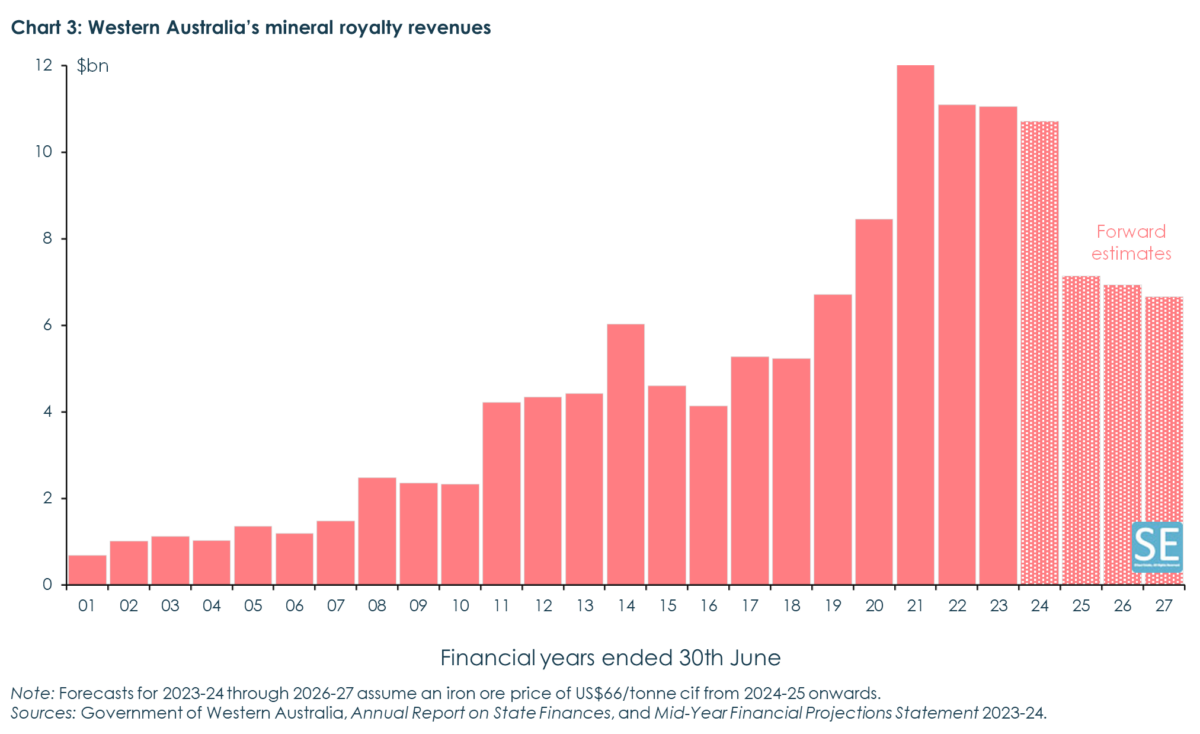

As a result of the enormous increase in the value of mineral production, the Western Australian State Government has reaped an enormous increase in revenue from mineral royalties – from less than $700 million in 2000-01 to an average of almost $11.5 billion a year over the past three years (Chart 3).

Western Australia’s right to levy these mineral royalties is not in question. Under Australia’s legal system, Western Australia’s mineral resources belong to the people of Western Australia, and mineral royalties are a payment by mining and energy companies to the Government of Western Australia for the use of those resources.

Western Australia’s right to levy these mineral royalties is not in question. Under Australia’s legal system, Western Australia’s mineral resources belong to the people of Western Australia, and mineral royalties are a payment by mining and energy companies to the Government of Western Australia for the use of those resources.

But this bonanza has substantially enhanced Western Australia’s capacity to fund the provision of public services and infrastructure to its citizens.

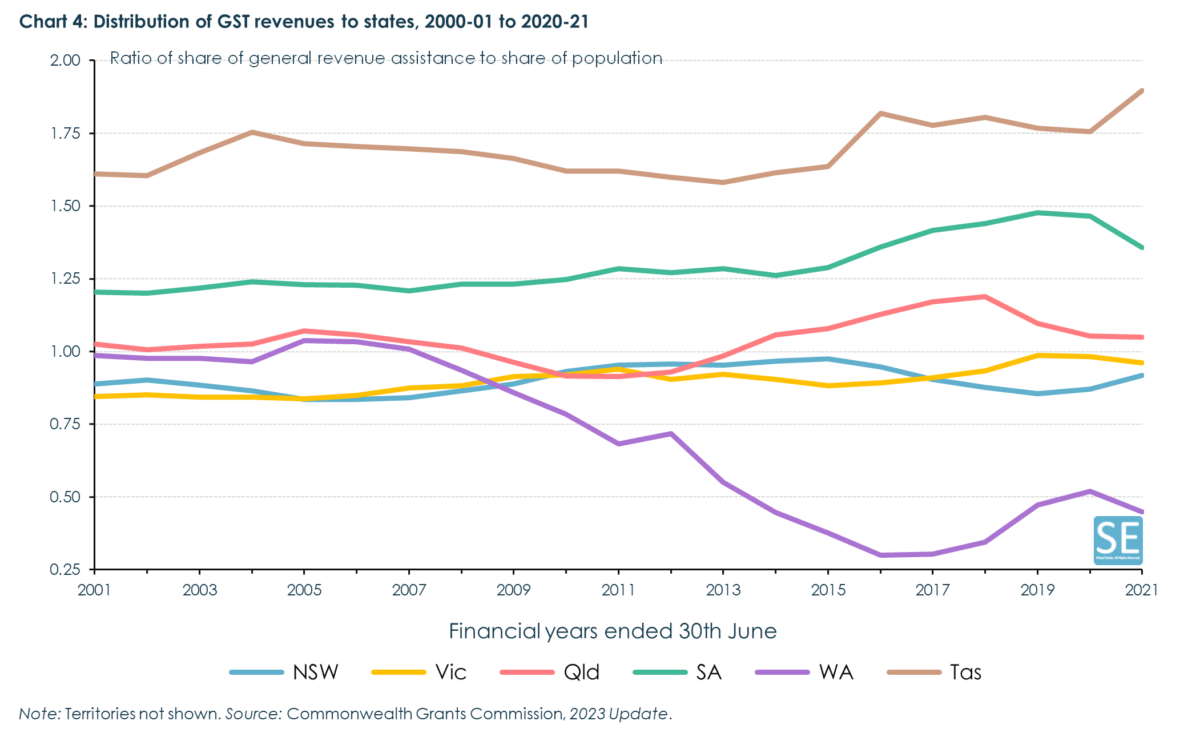

It is therefore entirely in keeping with the principles of ‘horizontal fiscal equalization’ from which Western Australia benefited for the best part of seven decades that Western Australia’s share of revenue from the GST should have fallen significantly, relative to its share of Australia’s population – as indeed it has done since 2008 (Chart 4).

Successive Western Australian Governments have bleated that this is ‘unprecedented’ and ‘unfair’ – that “we are getting less than 30 cents in the dollar of our GST”.

Successive Western Australian Governments have bleated that this is ‘unprecedented’ and ‘unfair’ – that “we are getting less than 30 cents in the dollar of our GST”.

Yes, it is ‘unprecedented’ in the sense that there has not been any previous instance of a state or territory receiving as small a share of GST revenues (or, prior to 2000, other forms of ‘untied’ grants from the Commonwealth), relative to its share of the national population, as Western Australia has received since 2009.

But that’s only because, as shown earlier, there has never been an instance where one state has been so much wealthier than, and its ‘fiscal capacity’ so much greater than that of, other states and territories as Western Australia has been over the past 15 years. That’s unprecedented, too.

Far from being ‘broken’, as successive Western Australian governments have tried to argue, the system of ‘horizontal fiscal equalization’ was working exactly as it should have.

It was no more ‘unfair’ for Western Australia to be receiving “as little as 30 cents in the dollar” of what it (allegedly) “pays” in GST, than it was for Western Australia to have received over 50% more than it would have under an equal per capita distribution of ‘untied’ Commonwealth grants between 1947 and 1970, as shown in Chart 1 above.

Certainly, no Western Australian state government ever complained about that.

And in truth, no-one actually knows how much GST has been paid by Western Australians, or the residents of any other state. The Australian Taxation Office doesn’t publish a state-by-state breakdown of GST revenues, because it doesn’t know either. When I buy wine from Margaret River wineries, as I often do, the GST I pay on that purchase would be recorded as having been collected in Western Australia (if such records are kept) – even though it has actually been paid by a Tasmanian. When a Western Australian books a flight between Perth and Sydney, the GST on that airfare is recorded as having been collected in Sydney or Queensland, depending on whether the booking is with Qantas or Virgin, even though it has actually been paid by a Western Australian.

I don’t blame successive Western Australian state governments, of both political persuasions, for making these specious arguments for over a decade. Voters expect their state governments to screw as much money out of the Federal Government as they possibly can.

Rather, it is Federal politicians, of both political persuasions, who deserve blame for failing to see through these arguments, and for elevating narrow political calculations above the requirements of good public policy, and the national interest.

Western Australia finally found its man in Scott Morrison, as Treasurer in the Turnbull Government, a government which had five Western Australians in its Cabinet. In May 2017, Morrison tasked the Productivity Commission with undertaking an inquiry “into Australia’s system of horizontal fiscal equalisation (HFE) which underpins the distribution of GST revenue to the States and Territories”, with Terms of Reference which read as if they had been written by the WA Treasury, so replete were they with the arguments which Western Australia had long been using in support of its demands for changes in the arrangements from which it had, until the onset of the ‘mining boom’, benefited so much.

The Productivity Commission inquiry was conducted in a most un-PC-like fashion, with scant regard paid to the evidence presented to it. In particular, having been invited by the Terms of Reference to consider whether the long-standing HFE principles created “disincentives for reform, including reforms to enhance revenue raising capacities or drive efficiencies in spending”, the Commission couldn’t find any evidence to support this assertion.

But rather than acknowledging that there was in fact no evidence to support it – as Nick Greiner and John Brumby had, when asked by Wayne Swan to review the HFE system in 2011 – the Commission instead asserted that “absence of evidence doesn’t mean evidence of absence”. That was of course the same logic that George W Bush, Tony Blair and John Howard used to justify the invasion of Iraq in 2004, even though United Nations weapons inspectors had been unable to find any evidence that Saddam Hussein possessed “weapons of mass destruction” (and, as it turned out, he didn’t). Yet despite that comparison being pointed out to them at a public hearing on the Commission’s ‘Preliminary Draft Report’, the Commission repeated the same glib phrase, verbatim, in their Final Report.

It’s my understanding that there was considerable disquiet among some of the staff who worked on that inquiry with the way in which it was conducted – and that one of them subsequently resigned in disgust.

The Morrison Government’s response to the Productivity Commission’s report, resulted in two major changes to the principles on which the revenue from the GST would be distributed among the states and territories henceforth.

First, instead of raising the ‘fiscal capacity’ of each state and territory to that of the fiscally strongest state – which in most years since 2008 has been Western Australia – the benchmark would become the stronger of either New South Wales or Victoria. This change would be ‘phased in’ over six years, beginning in 2021-22.

Second, a ‘floor’ would be placed under the ‘relativity’ of each state and territory’s GST share – that is, the proportion of GST revenue which it would receive, relative to its share of Australia’s population – such that in 2022-23 and 2023-24 no state or territory could receive less than 70%, and from 2024-25 less than 75%, of what it would have received under an ‘equal per capita’ distribution of GST revenues. The only state to which this ‘floor’ would apply was, of course, Western Australia. Between 2019-20 and 2021-22, the Morrison Government made additional untied grants to Western Australia to achieve the 70% ‘floor’, before the phasing in of these changes had commenced.

These changes (when fully implemented) will have two significant practical consequences. First, when Western Australia is the fiscally strongest state – as it has been for most of the past decade, and seems likely to be over the remainder of the current decade – a smaller proportion of the ‘GST pool’ will be used to raise the ‘fiscal capacity’ of the fiscally weaker states, because their ‘fiscal capacity’ will now only be raised to that of the stronger of New South Wales or Victoria, rather than to that of Western Australia, as would have occurred under the principles which applied before 2022-23. And second, if Western Australia’s share of the ‘GST pool’ were to fall below 70% (in 2022-23 or 2023-24) or 75% (in 2024-25 or beyond) of what it would have received under a notional equal per capita distribution, then its share will be raised to the level dictated by that ‘floor’, and the other states’ and territories’ shares reduced commensurately.

Conversely, however, if Western Australia is not the fiscally strongest state – as would likely be the case in the event of a sharp fall in iron ore prices – then its fiscal capacity, along with that of all the other states and territories, would be raised to that of the stronger of New South Wales or Victoria.

In other words, “heads Western Australia wins – tails, the other states and territories lose’.

In order to cajole the other states and territories into accepting a set of arrangements which was (or should have been) so obviously disadvantageous to them, the Morrison Government agreed that the Commonwealth would ‘top up’ the ‘GST pool’ so that, until 2026-27, no state or territory would be worse off (that is, would get less revenue from the ‘GST pool’) than it would have done under the principles which applied up to 2021-22.

The projected cost of the ‘no-worse-off transitional guarantee’ was predicated on an assumption that iron ore prices would fall back to, and remain at, US$55 per tonne. That in turn meant that, in practice, Western Australia’s share of GST revenues wouldn’t fall below the 70% or 75% of equal-per-capita floors, and either NSW or Victoria (rather than Western Australia) would be the ‘standard’ to which all states’ and territories’ fiscal capacity would be lifted. And that in turn would mean that the ‘transitional guarantee’ wouldn’t cost the Federal Budget very much – just $8.95 billion over the ten years to 2028-29, according to the Morrison Government’s initial response (in July 2018) to the Productivity Commission’s Final Report on HFE.

As things turned out, the iron ore price didn’t fall back to US$55 per tonne, but has instead remained above US$100 per tonne for all but four months since June 2020.

And so the ‘transitional guarantee’ has cost far more than originally envisaged – because the 70% floor for Western Australia’s share has been binding, and because the fiscal capacity of the eastern states and territories hasn’t been raised to that of the fiscally strongest state (Western Australia), as would have been the case in the absence of the changes legislated in 2019.

Inclusive of the Albanese Government’s decision to extend the ‘no-worse-off transitional guarantee’, the changes legislated in 2019 are now estimated to cost the Federal Budget $39.2 billion over the 12 years to 2029-30 (Chart 5).

That represents a transfer of almost $40 billion from the Federal Budget (which ran budget deficits totalling $252 billion between 2019-20 and 2021-22, and which after recording surpluses in 2022-23 and, probably, 2023-24, was most recently projected in the 2023-24 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook to incur deficits totalling $189 billion between 2024-25 and 2029-30) to the Western Australian state government – the only government in Australia, and one of very few in the world, which is running and expects for the foreseeable future to run persistent budget surpluses – so that they can run even bigger ones.

It represents a transfer of almost $40 billion over 12 years to the government of the richest state in Australia, which (as measured by per capita gross product) is richer than the rest of Australia by a vastly larger margin than any other state has ever been, at least since Federation, so that the citizens of that state can enjoy better public services and lower levels of state taxation than the citizens of the rest of Australia.

How that can be reconciled with any sensible concept of equity, let alone fiscal prudence, is surely beyond comprehension.

So why did it happen?

The answer lies in the crudest of political calculations, made by politicians on both sides of the Federal Parliament.

Since the 2013 election, the Liberal-National Party Coalition had held all but three of Western Australia’s seats in the House of Representatives. After their narrow victory in 2016, they knew that if they were to have any chance of retaining government at the 2022 election, they needed to retain all eleven of the 15 WA seats which the Liberals had won in 2016.

Conversely, the Labor Opposition knew that if it were to have any prospect of winning government at the 2019 election, they had to win at least some of those seats from the Liberals.

Thus the Orwellianly-titled Treasury Laws Amendment (Making Sure Every State and Territory Gets Their Fair Share of GST) Bill 2018 passed both houses of Federal Parliament with overwhelming majorities.

And the same grubby political calculus applied ahead of the 2022 election. The Coalition couldn’t afford to lose any of the seats it held from Western Australia if it were to have any prospect of attaining a fourth term in government: and the Labor Opposition had to win some of them if it were to have any prospect of winning government at that election – which, aided by the extraordinary popularity of then Labor Premier Mark McGowan, they did.

The 2018 legislation provides for another inquiry by the Productivity Commission “to assess whether the “updated [sic] system” is operating efficiently, effectively, and as intended”, to be completed before the end of December 2016.

It’s not clear whether this wording precludes the Productivity Commission from inquiring and reporting on whether the “updated system” has resulted in “equitable” outcomes, or on whether the more-than-fourfold blow-out in its cost to the federal budget is at odds with the objectives of “efficiency” and “effectiveness”.

By rights, it should be allowed to consider such issues, and more. It is important that the Terms of Reference for this inquiry are not written in such a way as to pre-determine the outcome, as was the case with the 2017-18 inquiry.

Indeed, it might be sensible for the Productivity Commission – perhaps in conjunction with the Grants Commission – to be tasked with the objective of designing a completely new system, one which retains the objective promulgated by the Grants Commission in 1936 of ensuring, as far as possible, that each state and territory has the capacity to provide its citizens with a similar range and standard of public services, without imposing state taxation regimes of very different severity, but does so in a simpler and more transparent fashion than that which had evolved over decades.

It could for example consider whether the use of ‘proxies’ for ‘fiscal capacity’ such as gross state product per head (bearing in mind that most state taxes are paid, at least in the first instance, by businesses, not households) might result in a simpler, more transparent, more predictable and more comprehensible (to the general public) way of assessing differences in revenue-raising capacity. Similarly it could consider whether there might be simple but nonetheless suitable proxies for differences in ‘expenditure needs’ – such as the proportions of state and territory populations over the age of 65 (and perhaps also over 80) and under the age of 16, the proportion classified or identifying as Indigenous, and the proportion living with disability.

But above all the Review should be conducted with a clear consciousness that it is considering the largest single expenditure item in the Federal Budget – and hence that its conclusions will be of enormous import.